Annie Ernaux has lived in Cergy, a new town situated 30 kilometres north-west of Paris, since 1975. This town plays a significant role in her work and in the writing process since she has written most of her books in her house there. She discusses the importance of Cergy and of her house for her creativity in the documentary film Les Mots comme des pierres (‘Words as heavy as stones’) by Michelle Porte, and the book of the interviews made for the film: Le Vrai lieu (‘Where I really live’). Cergy is also a lieu de mémoire or repository of memory for Ernaux, a place which represents both continuity and change. She has often expressed her attachment to Cergy and her rejection of the notion of such spaces on the edge of Paris as non-lieux or non-places. In one programme she becomes a guide to the town and its environs; in another she reveals her favourite haunts. In Régis Sauder’s film J’ai aimé vivre là, Ernaux’s texts and voice become a guide to Cergy, its places and inhabitants.

Cergy is also a peripheral place, situated outside Paris, a contemporary, cosmopolitan new town, that has provided the raw material for Ernaux’s two diaries of the outside: Journal du dehors (Exteriors) and La Vie extérieure (Things seen) and her diary of visits to the hypermarket Regarde les lumières mon amour. These texts consist of vignettes of Ernaux’s encounters in spaces such as public transport and shopping centres, as seen in the extracts below:

Exteriors [Journal du dehors]

“Memories as I am driving past the black 3M Minnesota office building with all its glass windows lit: when I first moved to the New Town, I would invariably lose my way but would go on driving, too panicked to stop. In the shopping mall, I would make sure I knew exactly through which door I had entered – A, B, C or D – so that I could locate the same exit later on. I would also try not to forget in which row of the parking lot I had left my car. I was afraid of having to wander under the concrete slab until nightfall without ever finding it. So many children got lost in the supermarket.” (Exteriors, trans. Tanya Leslie, Seven Stories Press, p. 26)

“On a sunny day like today, the seams of buildings lacerate the sky, the glass surfaces radiate light. I have lived in the New Town for twelve years, yet I still don’t know what it looks like. I am unable to describe it, not knowing where it begins or ends; I always drive through it. I can only write down, ‘I went to the Leclerc hypermarket (or to the Trois-Fontaines shopping mall, to the Franprix in Les Linandes, etc.), I turned back on to the freeway, the sky was purple beyond the Marcouville highrise apartments (or on the 3M Minesota façade).’ No description, no story either. Just moments in time, chance meetings. Ethnowriting.” (Exteriors, trans. Tanya Leslie, Seven Stories Press, p. 56)

“At Hédiard, in the smart, fashionable area of the New Town, a black woman wearing a boubou walked into the store. Immediately, the manager’s gaze became razor sharp, relentlessly pursuing this new client, whom one suspects has come to the wrong store, who doesn’t realize she is out of place.” (Exteriors, trans. Tanya Leslie, Seven Stories Press, pp. 66-7)

“At Super-Discount, young cashier, maybe a temp, is laughing with some people she knows, two girls standing beside her. The customers waiting in line are visible annoyed: it’s clear she doesn’t give a damn about us, she’s just ringing up the items, period. People resent her openness.

In a subway car, a boy and a girl argue and stroke each other, alternately, as if they were alone in the world. But they know that’s not true: every now and then they stare insolently at the other passengers. My heart sinks. I tell myself that writing is this for me.” (Exteriors, trans. Tanya Leslie, Seven Stories Press, p. 81)

“On the RER a young man, tall, with sturdy legs and thick lips, occupies a seat giving onto the aisle. Across the way, there’s a woman with a two or three-year-old boy on her lap; he is looking all around, sort of stunned, his eyes filled with wonder. Then he asks ‘how do they close the doors.’ It’s probably the first time he has been on the RER. Both of them, the young man and the little boy, take me back to moments in my life. First, to the year when I took my baccalauréat, in May, when D, a tall boy with big lips like this guy sitting over there, used to wait for me after high school, near the post office. Then, to the days when my own sons were small and discovered the world.

On other occasions, a woman waiting at check-out desk would remind me of my mother because of the way she moved or spoke. So it is outside my own life that my past existence lies: in passengers commuting on the subway or the RER; in shoppers glimpsed on escalators at Auchan or in the Galeries Lafayette; in complete strangers who cannot know that they possess part of my story; in faces and bodies which I shall never see again. In the same way, I myself, anonymous among the bustling crowds on streets and in department stores, must secretly play a role in the lives of others.” (Exteriors, trans. Tanya Leslie, Seven Stories Press, p. 95)

Things seen [La Vie extérieure]

“The sensation of time passing is not inside us. It comes from the outside, from children who grow up, neighbors who leave, from people growing older and dying. Bakeries that close and are replaced by driving schools or television repair shops. The cheese department moved to the back of the supermarket, which is no longer called Franprix but Leader Price.” (Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky, University of Nebraska Press, p. 10)

“Today, for a few minutes, I tried to see all the people I ran into, all strangers. It seemed to me that, as I observed these people in detail, their existence suddenly became very close to me, as if I were touching them. Were I to continue such an experiment, my vision of the world and of myself would turn out to be radically transformed. Perhaps I would disappear.” (Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky, University of Nebraska Press, p. 13)

“The cashiers at Auchan say hello at the exact moment when, having given the previous customer the receipt, they plunk your first item on the conveyor belt. Try as we may to place ourselves in their field of vision, right across from them, sometimes for more than five minutes, it is only at that moment when they begin to ring up our purchases that they seem to discover us. This strange and ritual blindness reveals that they are only obeying a requirement forcing them to be polite. From the point of view of marketing, we only exist at the moment when containers of detergent and yogurt are exchanged for money.

The hope, always in vain, of having nothing more to note, to no longer be swallowed up by anything whatsoever in this world, by the wave of anonymous people that I encounter and of which, for the others, I am a part.” (Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 29-30)

“Absolute silence where I am right now, in my house, a point in the indeterminate space of the new town. Experiment: via memory travel through the territory surrounding me, and in doing so describe and define the expanse of real and imagined space that is mine in the city. I go down as far as l’Oise – here is Gérard Philippe’s house – cross over, survey the outdoor recreational area at Neuville, return via Port-Cergy, dash off towards l’Essec, the areas of Touleuses and Maradas, pass the Pont d’Éragny – I am in the Art de Vivre shopping centre – return via Highway A15, turn off through the countryside to reach Saint-Ouen-l’Aumône, the Utopia Cinema, and Maubuisson Abbey. I pass over Pontoise in all directions, continue to Auvers-sur-Oise, go up the church hill, toward the cemetery, Van Gogh’s grave covered in ivy. I return by the same road along the Oise, making a brief stop at Osny. I take the wide avenues leading to the center of Cergy-Préfecture: Trois-Fontaines, the Tour Bleue, the theatre, the conservatory, and the library. I follow the RER line and the cavalcade of pylons to Cergy-Saint-Christophe, the big clock at the station. I walk along the street that leads me to the Tour Belvédère and the columns of the Esplanade de la Paix, from where an immense horizon unfolds, with, at the end, the shadows of la Défense and the Eiffel Tower.

For the first time, I have taken possession of space that I have been traveling through for twenty years.” (Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 59-60)

“Sales. All entrances to theTrois-Fontaines parking lot are blocked by lines of cars. People want to be the first to throw themselves at the clothes, dishes, like plunderers in a conquered city. The aisles are inundated by a flood of people, entire families with children in strollers, groups of girls. In the stores, frenzy. A tremendous desire to acquire fills the air.

The shopping center has become the most familiar place in this end of the century, like the church in times past. Chez Caroll, Froggy, Lacoste: people are seeking something to help them live, relief from time and death.” (Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky, University of Nebraska Press, p. 80)

“In the evening, the trip back by RER is broken up into two phases. Up until Maisons-Laffitte, sometimes even up until Achères, takes the same amount of time as the trip out: no waiting. The traveling time, accepted, imperceptible, where people can think more or less. In the final ten minutes before arriving at the destination, there is another phase in which nothing exists except the need to get there. The regular movements of the train, the increasingly less built-up landscape, the stretch of fields, from the perspective of the inner clock everything seems slowed down. Impossible to think of anythig during this time period. Longing only for the moment to leave the train, climb up the steps toward the exit, go through the turnstile, the cool air of the parking lot, the car. Hardly clear images, just an instinctive thrust toward what is a form of happiness. Each evening the same empty ten minutes: pure waiting.” (Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky, University of Nebraska Press, p. 82)

“Visible on a wall at Cergy station: the half-folded legs of a man in blue corduroys, between which are squeezed those of a woman wearing a dress with small white and green checks. The woman in seen from the front, the last buttons of her dress are open on her bare legs. It is a hippy fresco, dating from the late seventies, which will soon be erased when the station is renovated.

Someone has thrown red paint at the dress, at the place where the vagina would be, it forms a bloody spatter.” (Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky, University of Nebraska Press, pp. 91-92)

Honorary degree awarded by the Université de Cergy-Pontoise

In 2014, as part of the conference ‘En soi et hors de soi: l’écriture d’Annie Ernaux comme engagement’ [Commitment in the works of Annie Ernaux] which took place at the Université de Cergy-Pontoise, Annie Ernaux was awarded an honorary doctorate. We publish below the awards speech written and given by Pierre-Louis Fort, lecturer at the Université de Cergy-Pontoise, co-organiser of the event, and the author of many essays on Ernaux

Dear Annie Ernaux,

I’m not going to begin my remarks by going back over your career – of which I could only give a partial and prosaic account. Nor will I take us through the sum of your work, as we have just had that immense pleasure over the past two days – and I’m sure we could have gone on even longer, so rich were the exchanges and stimulating the contributions.

Rather, I would like to begin this address by thanking you for accepting this doctorate, a gesture which honours us at UCP all the more because we know how disinclined you are to accept honorary distinctions. You did however state in a newspaper a few months ago that you would be making us the exception:

I am going to receive the title of honorary doctor of the University of Cergy-Pontoise during an international colloquium being organised around my work in November in Cergy. Resistant to all forms of honorary award, it is the only one I will accept. Because it makes sense to do so.[1]

I think that, for us too, it makes a lot of sense. For all of us together here today in Cergy, whether just passing through, here for work, newcomers who have adopted Cergy, or longer-term residents, we are all at any rate this evening ‘Cergyssois’ in spirit.

It makes sense because it pays homage to the author of a rich, bold and powerful body of work. It also makes sense because it is today presented to you on your own ground, in two ways: at the University which has adopted your work as its own, in its research and teaching; and in this new town which has been yours for such a long time and about which you very recently said:

[…] as a child, as a teenager, my dream was to get to Paris. […] Paris, city of dreams, only 30 kilometres away from where I am now as the crow flies and yet I am still on the outside. And I no longer want to break in. It is as if I have found my proper place in this new town Cergy, the place where I feel at home. When I first arrived, I didn’t imagine staying here for so long. I believe, even, that that would have seemed unthinkable to me. It did not figure in my future, nor in my children’s future…[2]

Cergy. It is as a reader that I became acquainted with this town – from reading your work, well before coming to work here by an ‘objective chance’[3]. My very first visit is closely linked to your writing and dates back to the beginning of the 2000s. At that time I was working on a critical edition of A Woman’s Story[4] and Véronique Jacob, the collection’s editor, suggested that I interview you. On the phone you had explained to me how to get here by train and said to take care to get off at ‘Cergy Town Hall’ and not at ‘Upper Cergy’. This precision preoccupied me throughout the journey, during which, of course, I was thinking about scenes read in Things seen or Exteriors.[5] Picture the arrival: you in graceful silhouette at the foot of the escalator; me, uneasy and apprehensive, raising my hand tentatively to show it was me you were waiting for.

I must have the tapes of our interview somewhere but I prefer to treasure a more hazy memory of those few hours, which I found to be both awe-inspiring and heart-warming. My impressions of our discussion, in your kitchen and living room, with the cat quietly observing us, have become a little blurred. I no longer remember the return journey, except that I thought what a wonderfully fruitful meeting it had been, that this exchange with the author – which can sometimes be quite off-putting – had in no way diminished the texts for me, with their profound beauty and incomparable accuracy. To the extent that, on reading A Man’s Place[6] when I was 16, I was struck by an immediate resonance with some of the places in my childhood, in my history, struck also and above all – as on each subsequent occasion – by this writing which resonates in such an illuminating way, with its capacity to make us ‘hallucinate’[7] images from our own memories.

Forgive me for continuing to reel off my memories, but let me recall just one more, not because it evokes Cergy but rather because of the way in which it highlights your generosity and your care for others. You attended my PhD viva (now several years ago), subjecting yourself stoically to several hours of this ritual, saying mischievously to me: ‘Your thesis is based on Marguerite Yourcenar, Simone de Beauvoir and me. How could I not come then, given I’m the only author of this lot still left standing?’ I can tell you now that your presence then was very precious to me, on a scholarly, literary and human level. It clearly demonstrates your readiness to give of yourself, which I can’t mention without, again, referring to your books. In A Woman’s Story you said: ‘Isn’t writing also a way of giving’[8], no question mark, because the question carries its own reply. I think that the question mark is today even less appropriate. Because this idea of ‘giving’ came up with everyone I spoke to.

And when I say everyone, I am thinking specifically of the family, understood in the sense you gave to it in the preface of the volume of the proceedings at Cerisy[9] – this family that I have not failed to consult, by email, to involve them in this dedication, because I wanted my speech to be made up of many voices in addition to my own.

Voices in polyphony celebrating both an oeuvre and a person who has affected us profoundly. Let me begin by allowing one of your longest-standing associates speak: ‘Annie Ernaux deserves every possible honour, but – as people used to say about Sartre – even every possible honour cannot convey what Annie Ernaux represents. And what’s more: she doesn’t like marble statues’ (Fabrice Thumerel). No marble statue then but, rather, let me give expression in this lecture hall to some gentle voices.

I think that one of the first things repeatedly mentioned in the emails people sent me is your generosity. The word appeared frequently in so many replies, notably this one:

‘The word which comes to me straightaway when I think of Annie Ernaux is generosity: in her work which she gives to her readers, enabling them to break away from obvious or more insidious forms of alienation; from her experience as a woman and an intellectual which she passes on in order to improve the place of women in society, their coming to awareness and freedom, notably sexual, but not only that, the generous giving of her self above all, who never fails to reply to a letter, who reads what one sends her, who takes the time to give her point of view, her advice, who encourages and guides without ever being burdensome nor setting herself up as a model, and in a perfectly free manner, without taking her time into account’ (Anne Coudreuse).

And the author of these words is not the only one to think so. Others have also commented that you are ‘someone who can speak of her work and her writing in a straightforward, effective and generous manner’ (Françoise Simonet-Tenant), and that what is immediately apparent is your ‘generosity, the undivided attention you bestow on others, an even-handed affection, such a charismatic presence’ (Francine Dugast). There are also fine words on ‘the warm generosity, smile and affection she conveys as a person above and beyond being an author’ (Francine Best). This, in turn, is confirmed by this further comment underlining the extent to which you are ‘concerned about the wellbeing of others, attentive’ and ‘despite your renown, very unassuming, no vanity’ (Lyn Thomas).

Some have reverted poetically to the place you call home and its creative significance: ‘A house in Cergy, on the banks of the river Oise: water, always there, a calming and tempering influence’ (Jean-Claude Lescure). Other contributions, of course, focus on your work itself, on its rich originality. For example: ‘In an era which is individualistic in the extreme, which encourages narcissism above all, Annie Ernaux has always measured the relevance of life-writing, as a function of the level of challenge it confronted her with. Thanks to that, she has given her readers writing which illuminates and liberates’ (Marie-Laure Rossi). Because, what this amounts to, in fact, is the extent to which we take on and understand her writing: ‘For me, the work of Annie Ernaux goes right to the heart of what matters. This is without doubt the most general definition I would give it, one which comprises at once all the themes she tackles, namely people’s relationship with their childhood and social background, questions of desire, the couple, intimacy, the body – obvious truths that are in fact not obvious since the situations described, including the way we perceive our town, other people, that familiar experience of the unknown that makes up our everyday world, unsettle the subject who experiences them’ (Bruno Blanckeman). Others wrote that you are ‘a writer who takes risks, puts herself in danger, approaches writing in an inventive and fearless manner, not a conformist, one who confronts taboo subjects, who revives the way we look at things, who enables us to see and who involves the reader, encourages them in turn to take a retrospective look at the self, one’s history, and who ultimately prompts the desire to write oneself’ (Violaine Houdart-Mérot).

Several remarks focus, naturally, on your writing: ‘getting right to the heart of things, […] using language with a kind of simplicity which is not simplistic, but has a sense of the formulation that can encapsulate events and situations in a few sentences, a few expressions, allowing the substantive part to come through, a layer of underlying meaning, hidden beneath simple situations’ (Bruno Blanckeman), a ‘style of writing very close to reality, revealing the suffocating constraints (what Bourdieu calls “symbolic violence”) of the world order’ (Nathalie Froloff), ‘prose which often makes me say: “that’s exactly how it is!” ’. This effect of capturing something is intrinsically linked to the emotion which bursts out in an even more powerful way in the books because it is held in check, restrained. Ernaux’s writing brings both clarity and sheer delight’ (Aurélie Adler). This leads us to this other – effectively methodological – aspect, of your work: ‘Annie Ernaux is someone who manages to put into words what we feel albeit obscurely, what we haven’t succeeded in articulating’ (Françoise Simonet-Tenant), or again: ‘Annie’s work, in my eyes, has the knack of questioning and working on those contradictions which, when it comes down to it, are not that: boldness and reserve; gentleness and forcefulness; simplicity and complexity. In so doing, she reminds us that writing’s task is to speak to us of life, that it has a way of making us feel – and making us understand – life itself in the fullest sense of the word’ (Thomas Hunkeler).

There is no doubt in our minds that what you have done for literature is revolutionary: ‘Just as we read Zola to transport us back to the Second Empire, so will future generations read Annie Ernaux to be plunged into the second half of the twentieth century’ (Michèle Bacholle-Boskovic). And again: ‘I don’t think it an exaggeration to say that her books have opened up a new pathway in literature, and beyond’ (Elise Hugueny-Léger). And again: ‘The work of Annie Ernaux offers a lot to her reader. And what she provides, amongst other things, is a newfound confidence in literature’ (Yvon Inizan).

To read your work, Annie, is to be displaced, overwhelmed, changed: ‘It is difficult to express what Annie Ernaux means for me, who discovered her books when I was 14 and whose texts influenced much more than my professional career, but also my way of seeing the world’ (Elise Hugueny-Léger). ‘No other author explores questions of class, the condition of women or sexuality in such an incisive and poignant way as Annie Ernaux. Her masterly work touches me deeply’ (Barbara Havercroft). I would also like to quote, in this context of reading and the immediacy of recognition, this short extract: ‘I was 30 years old when I first read Annie Ernaux and the first book of hers I discovered was Happening[10]. Immediately, the author’s voice was in evidence, inhabiting the page: completely authentic, neither complacent nor wrongly understated, neither self-pitying nor detached. A plainsong, capable of tracing an immediately recognisable route straight to the core of what constitutes a life, with the dexterity of a brushstroke. Emotions (violent), sorrows (profound) and desires (passionate or lethal), raw and uncompromising are brought to bear. Nothing stands in the way, nothing prevents this. Such an impressive capacity to give form to lived experience […]’ (Véronique Montémont).

We have all, thanks to you, had a reading experience of such power, that each text, in addition to its universality, is uniquely received by each reader: ‘Reading her work thus always produces a shock in readers who recognise themselves in the intimacy of reading as if the book was being addressed to them alone – the very nature of great books’ (Nathalie Froloff). ‘Annie Ernaux brings me closer to my own life, she gives me strength. With The Years[11], she became for me one of the rhythms of time’ (Tiphanie Samoyault).

You are one of those authors, Annie, whose next book is always eagerly awaited: ‘Annie Ernaux is one of those authors I follow in delightful anticipation, the expectation of the next book, like an encounter, to be read in one go. She is an author who – quite simply – is part of my journey through life’ (Isabelle Roussel Gillet). You belong to those writers who take things forward and help to further our understanding: ‘Annie Ernaux is first and foremost from my point of view a figure who is key to helping me understand my parents’ generation, and gives me a better grasp of the situation of women in society – their political and social struggles which need to be constantly reviewed and pursued’ (Aurélie Adler), a writer who equips us: ‘Annie Ernaux’s writing has the same impact on me as The Second Sex:[12] key arguments in defence of ideas which I knew I had but which until then were at the level of humanist sentiments based on platitudes’ (Pierre Bras).

I will finish with the other delight, beyond reading your work, which we have in knowing you. As witnessed by the following quotations: ‘Annie Ernaux, with her striking blue eyes and discerning gaze, scrutinises the world and other people with extraordinary attention, focussing from time to time on something going on, giving life to her face’ (Catherine Douzou). Or again, ‘Annie Ernaux, at once both intense and light-hearted, serious and ironic, passionately alive’ (Bruno Blanckeman). And another: ‘She has an astonishingly friendly and uncomplicated manner, an elegance that shines through, an open determination to live life freely, a clear focus, “life clarified”[13], razor-sharp in peeling back mere appearances’ (Francine Dugast). But what we also love is your ‘sense of humour, a heart-warming laugh and smile’ (Lyn Thomas), this ‘peal of laughter’ (Francine Dugast) which expresses ‘quite simply, life’ (Isabelle Roussel Gillet). Let me quote another example: ‘Annie very quickly became for me an authentic voice which goes to the heart of things, with no hesitation, with warmth and a smile. One single memory – since she doesn’t go in for statues. In Arras, during the first international colloquium on her work, she said to Pierre-Louis and me, young researchers who were teasing her: Watch out, or I’ll put you between the covers of my diary! (burst of laughter)’ (Fabrice Thumerel).

I think we can attest without the slightest hesitation that ‘we are very lucky indeed to know you and also to bear testimony to your extreme generosity of spirit with regard to readers and critics, and to your constantly renewed curiosity in the face of the rush and noise of the world’ (Nathalie Froloff). All of us, today, want to say: “Thank you”. ‘As Christian Baudelot proclaimed at Cerisy: “Thank you, dear Annie Ernaux, for having spoken so well of US.” I make that declaration my own, our own’ (Francine Best). ‘It is difficult to find the right words to thank writers who have created literature that surpasses itself , writers who have put within our grasp, as has Annie Ernaux, more than books alone, but a way of understanding our existence’ (Véronique Montémont).

You once proclaimed: ‘I wish that everyone could read Aden Arabie and The Watchdogs by Nizan,[14] and The Beautiful Summer and The Diary by Pavese.’[15]

I think that all of us gathered here today would like everyone to have read and to read, again and again, Annie Ernaux.

Pierre-Louis Fort, Cergy, 20 November 2014

Translated by Jo Halliday

[1] ‘Ma mémoire est liée à la ville nouvelle’, interview with Annie Ernaux, Le Parisien, 17 January 2014, http://www.leparisien.fr/espace-premium/val-d-oise-95/ma-memoire-est-liee-a-la-ville-nouvelle-17-01-2014-3501705.php.

[2] Annie Ernaux, Le Vrai Lieu, entretiens avec Michelle Porte, Gallimard, 2014, p. 14.

[3] The French term here ‘un hasard objectif’ is a reference to the surrealist writer André Breton, who used it to describe the strange and yet externally verifiable nature of coincidences.

[4] NdT/Translator’s note: This is the title of the translation of the novel into English by Tanya Leslie, Quartet Books, London, 1990. The critical edition of the novel referenced in French is: Annie Ernaux, Une Femme, Gallimard, coll. La Bibliothèque Gallimard n° 88, accompagnement critique par Pierre-Louis Fort, 2002.

[5] NdT/Translator’s note: These refer to texts at the beginning of the section above on Cergy.

[6] NdT/Translator’s note: This is the title of the translation of the novel into English by Tanya Leslie, Seven Stories Press London, 1992, Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020

[7] Annie Ernaux, L’Ecriture comme un couteau, Entretien avec Frédéric-Yves Jeannet, Stock, 2003, p. 41.

[8] NdT/Translator’s note: From A Woman’s Story, translated into English by Tanya Leslie, Quartet Books, London, 1990, p. 95.

[9] Bruno Blanckeman, Francine Dugast and Francine Best (eds.), Annie Ernaux: Le Temps et la Mémoire, Stock, 2014, p. 23.

[10] NdT/Translator’s note: This is the title of the translation of the novel into English by Tanya Leslie, Seven Stories Press, 2001, Fitzcarraldo Editions, London, 2019.

[11] NdT/Translator’s note: This is the title of the translation of the novel into English by Alison L. Strayer, Fitzcarraldo Editions, London, 2018.

[12] NdT/Translator’s note: This is the title of the translation of the book into English by Constance Borde and Sheila Malovany-Chevallier, Vintage, London, 2010.

[13] NdT/Translator’s note: This is an abridged phrase taken from Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time, Volume 6, Finding Time Again: ‘Real life, life finally uncovered and clarified, the only life in consequence lived to the full, is literature. Life in this sense dwells within all ordinary people as much as in the artist. But they do not see it because they are not trying to shed light on it.’ Translated into English by Ian Patterson, Penguin Modern Classics, London, 2002, p 204.

[14] NdT/Translator’s note: The titles of the translations of these texts, written by Paul Nizan, into English are: Aden Arabie, translated by J. Pinkham, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1968; The Watchdogs: Philosophers and the Established Order, translated by P. Fittingoff, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1972.

[15] NdT/Translator’s note: The titles of the translations of these texts, written by Cesare Pavese, into English are: The Beautiful Summer, translated by Peter Owen in 1955, rereleased by Penguin European Writers, London, 2018; This Business of Living: Diaries 1935-1950, translator unknown, Transaction Publishers, New Jersey, 2009.

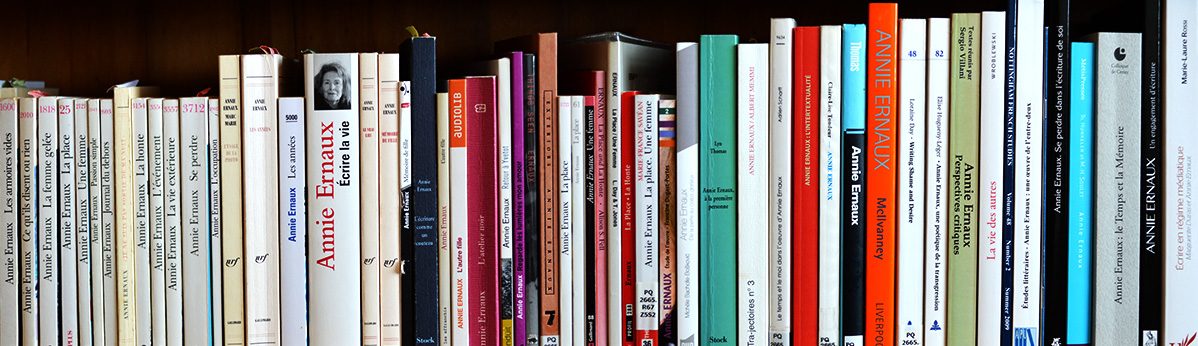

Image credit: Pierre-Louis Fort.