The Nursery

Who in Yvetot remembers the ‘Nursery’, that long stretch of allotments crossed by a path that linked the rue des Champs to the rue du Clos des Parts? From the latter you could get to them via a steep path with uneven steps made of randomly placed stones carved into it. At the top, along the ditch that marked the boundary between the nursery and the road, there was a row of huge beech trees that terrified me on days of high wind. My parents’ café and grocery shop was in fact just opposite the steep path, and from their bedroom window, upstairs, I could see all the gardens stretching out before me.

They were the property of two old ladies by the name of Fromentin. They rented them out to families in that part of the town for a sum no doubt considered reasonable given the huge advantage of being able to harvest fresh vegetables. Having a garden in the Nursery was a sought after privilege. From March to November, in the evenings after work, or on Saturday or Sunday afternoons, the men would arrive with their ordinary spades or Irish spades[1] on their shoulders and would return to their section, separated from its neighbour by a path or a low hedge. The wives or children would call by with the dog, to keep them company for a moment, bring a snack, pick beans or strawberries, or gather potatoes. I remember a couple, the F. – the woman was strong and got through more work than the man. In the summer they brought their cat with them, and refreshments, in the form of litres of wine, which poisoned their relationship. They fired off insults at each other, his favourite was ‘vieille trueille’, Normandy dialect for ‘vieille truie’ – old sow. But their garden was well looked after, and that made up for all the rest.

Because the gardens had to be clean, that is free of weeds, with perfectly straight rows thanks to strings held by two pegs pushed into the ground at both ends. The honour of the gardener was at stake. That of displaying the order and beauty of the vegetable beds, like unsigned paintings, that changed as the seasons passed.

My father’s garden was the first on the right as you went up the steep path, our neighbour cultivated the one next to it. I remember the seed packets stuck at the end of the rows, with their mysterious names: ‘all year round radish’, ‘lazy blond lettuce’, ‘straw yellow onions of all the virtues’. I remember the carpleuses (tiny caterpillars) hidden in the cabbage leaves, where raindrop pearls lingered.

At the entrance to the garden there were redcurrants, which we called ‘guards’, and green, velvety gooseberries. Not far away, a compost heap for the waste and the night soil, the latter sometimes poured directly onto the dug over soil of the last row.

My father grew carrots and leeks, turnips, shallots, garlic, spring onions, and parsley, sorrel, black radish, beans on canes, mange-tout, for shelling – which would be hung up to dry in the attic through the winter – ‘gourmet’ peas, new potatoes that we enjoyed with butter, and strawberries whose reddening fruit I looked out for under the leaves in June. He didn’t ‘do’ tomatoes, asparagus, spinach, cucumber or artichokes, declaring that ‘they don’t do well round here’.

In summer I would hear the dull, regular sound of his Irish spade flattening the earth.

Today the gardens have disappeared, replaced by a housing estate. The tall beech trees have been felled. But from the window of memory where I stand I can see the long green avenue of the Nursery, and at the end of the avenue the red sun setting over the hospice, whose Angelus bell would ring at half past six in the evening.

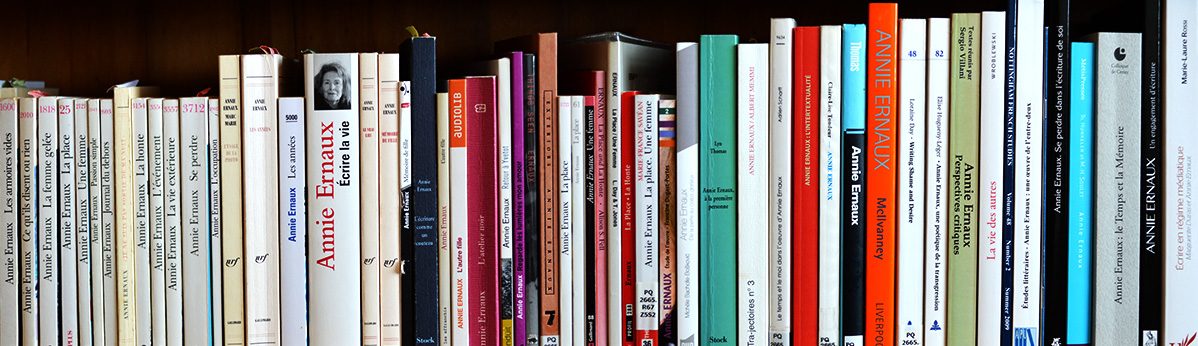

Original text, published for the first time here with Annie Ernaux’s kind permission, translated by Lyn Thomas. Translation first published here on 17 June 2020.

[1] Louchet in French, a long flat spade, variously known as Irish spade, Cornish spade or West Country spade in English [translator’s note].