On the beach of an island in the archipelago of Kerkennah, off the coast of Sfax, a little girl, about three years old, was found on the 24th December last year. Death by drowning. She was wearing a pink blouson jacket and tights.

Unlike Alan, the little Syrian boy of the same age, also found lying on a beach, in September 2015 in Turkey, wearing a red t-shirt and blue Bermuda shorts, and whose photo was circulated round the globe triggering huge emotion, the little girl from Sfax remained anonymous, like those many others, children, adults, whole families, who flee. No-one spoke of her in the French press until the reporter Nejna Brahim published an article about her on the site of an online newspaper in February this year. I don’t know whether the Italian or European press generally reported on this discovery. Tunisian papers doubtless did not, such is the extent to which fishermen bringing back lifeless bodies in their nets has become normalised. In fact the National Guard no longer even attends the scene when the drowned migrants are black. The little girl of Sfax, who was black, found drowned on a beach, is no longer even a ‘human interest story’[1] in the newspapers, whilst a cat run over by a high- speed train at Montparnasse station on the 23d January filled several columns of Le Figaro. Only the collective death of migrants is still noticed by the media – but till when? – amidst general indifference.

When I was asked to speak about territories of liberty, I thought of the little girl of Sfax, and about that principle of liberty enshrined in several articles of the European Convention of Human Rights, and in France emblazoned on public buildings, a principle that stops at the border. Not for all, and not for everything. Because, with goods circulating merrily from one continent to another, freedom, it seems is above all for things and money. Human beings are not so fortunate, especially and all the more so, if they are poor and black, since there is a disavowed but effective racial hierarchy. Sub-Saharan Africans, treated as chattels for centuries, do not even have this status on their doomed rafts: commercial cargo ships do not turn round to save them. Europe has become a fortress and the island of Lampedusa, its gateway, a huge detention camp, while the other nations remain silent.

Inhumanity begins with silence. We are, in the present moment, in danger of collective inhumanity in Europe. More and more, populations are surrounded by a gigantic, formless shadow agitated by numerous political parties on the promise of future power, and which seems to penetrate everything. This shadow can be summarised in one word: immigration. Is there time, before it’s too late, to realise that this shadow does not actually exist? Before the police start arresting immigrants – oh but they are already doing this! – before they arrest those who help them. From time immemorial there have been economic and cultural migrations. The Normans, my own ancestors, came here to Sicily. Today a quarter of the French population are immigrants or of immigrant descent. Far from impoverishing the countries who welcome them, the men and women, and then children contribute to the creation of wealth. Associations and volunteers who try to help migrants know that the latter have acquired an inner strength and vision of humanity that European countries would be wrong to deprive themselves of.

In the summer of 2016, on the occasion of the celebration of the Manifesto of Ventovene, which is considered to be the foundation of European federalism, an Italian newspaper asked me to write something. Just as today, I was unable to do anything other than to speak of the deaths of hundreds of migrants in the Mediterranean. However, an equally significant statistic: since the beginning of that same year 68 women had been killed by their partner in France, without any of these deaths appearing on the front page of the papers, just ‘human interest’ stories. What these two series of events have in common is the indifference to the facts, the silence signifying normalisation or at least habituation to these intolerable situations.

Seven years later, I will give a different report. Women have broken the silence. If I search today for the terrain of liberty it’s in the words of women that I find it. Voices that have risen up in the whole world as never before in history against masculine sexual violence, but also against political and religious domination. Injustice has been denounced as intolerable. In Iran, under the dictatorship of the mullahs, three words have blossomed: WOMAN, LIFE, FREEDOM, and men have joined women in a struggle which, although repressed by the authorities, is not over. Indeed this new feminist revolution is destined, through social networks, to reach all countries, and to question the patriarchal foundations of this society, made, as Simone de Beauvoir said 70 years ago, by men, for men. And it’s urgent to invent a world where little girls and boys no longer die off the coast of Sfax.

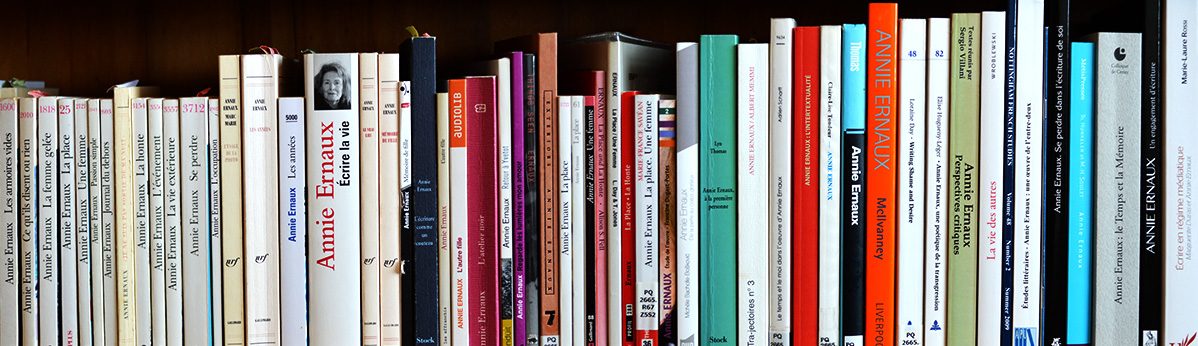

This text was written on the occasion of Annie Ernaux’s participation in the literary festival of Taobuk, in Sicily (June, 2023). The festival theme was ‘freedom’. Published here with the kind permission of Annie Ernaux. Translated by Lyn Thomas. Translation first published here on 4 July 2023.

[1] ‘fait divers’ in French