You’re sitting up straight in your seat, impassive. Shielded – against getting a cold head by the double protection of a wool cap and a fur hood – against getting your bag snatched because you were careful to place the strap over your head, while your gloved hand on the flap increases its security. No, the one who will it steal from you hasn’t been born yet. Behind your glasses, behind the two holes dug into the mask that makes you look like an old Indian, the two black marbles of your eyes weigh me up. Challenging me – because I dare to write about you – just as they challenge the passengers of the bus to look into the face of what they don’t want to see, something inadmissible, the fascinating obscenity of a time-ravaged face.

Your final face, the one that makes the earlier ones unimaginable, though verifiable in the photos stored in albums where you appear at every age, in resorts, alongside people who for the most part have since passed away. It doesn’t surprise you anymore. In the morning, you look coldly into the mirror at your skin whose every inch is cracked and crevassed; at your nose that has been erected by your sagging cheeks like a cliff above two deep furrows, though you’ve forgotten that, at the age of twenty, you saw in them the first signs of time, the first smile-forged wrinkles; at your lips now reduced to a thin line you no longer bother to pass lipstick over.

Tanned from winters in Courchevel, summers on a yacht, not bothering to protect yourself from the sun, which you were entitled to several months a year. Anyway, you never thought you were beautiful, didn’t want to be. Beauty is the dowry of poor girls, secretaries whose goal was to get their hands on the son of some wealthy family, for you it is something vulgar. You didn’t need beauty, or the higher education that allows scholarship-holders to meet a rich boy and get into a good family, although their table manners don’t fool anyone about their origins. You were a good match and in the église Saint Honoré d’Eylau you married someone that was well-suited, a proxy-holder at the Rothschild Bank. A solid union that left you, sixty years later and widowed, safe from need for centuries. Because others die, but you don’t, frozen in eternal old age, more enduring than the eternal youth promised by the Elisabeth Arden cream you used in your thirties.

I’m inventing a life for you, the life of your gaze on the number 72 bus. A gaze that judges, gauges and separates – separates you instinctively from all those who don’t show signs of belonging to your world. The unyielding gaze of eighty years of domination and passing down legacies and moral and financial certainties.

You are the overwhelming portrait of rich endurance. Of its arrogant, inaccessible evidence. My words bump up against it, as it was captured – naked and undeniable – by the camera flash. I hold your gaze but you’re stronger, you force me to the violence of words, you make me subordinate to your desire that I should expose my violence. Between you and me – you don’t know this – there’s something you think is completely irrelevant and unreal, an old-fashioned, Bolshevik thing that makes you and all your friends laugh today, though yesterday it – the class struggle – frightened you.

You make me remember servitude. Not for me, I escaped. For my aunts, placed as “domestic help” at the age of 12, for my father and uncles – “farm boys” until they went into the military, for my grandmother whom I saw washing other people’s sheets at the age of 73, for my mother’s older sister who always smelled of bleach from scrubbing tiles in the “nice houses”. An inherited memory of servitude that your air, your gaze, awaken from the depths of childhood.

You force me to remember the shame that you never experienced, since you were always the one who inflicted it – innocently though, so you couldn’t admit it during confession – just with a look of disdain for bad girls, uneducated, “never a hello or good-bye, you know what that means”, my shame as a teenage girl outside her own milieu, the milieu of the “ordinary people” as you say, certain that you are referring to them with affection and kindness.

You are my anger.

You are my revolt against the world order that gave you that look. Looking at you sets it on fire. In a sense, you could once again take pride in your power, but it’s not yours, it belongs to the photo. More precisely, the mysterious, admirable will of the photo that threw me into battle with you and forced me to reveal my truth. Your will remains mute and elusive.

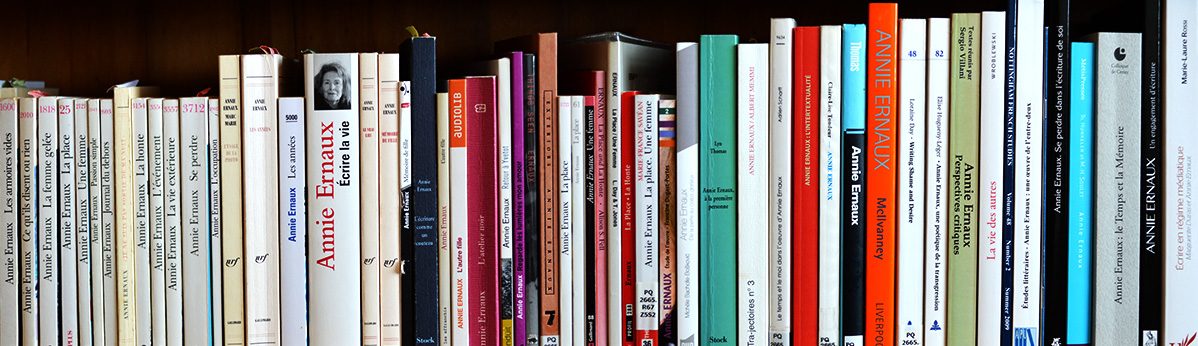

Translated by Dawn Cornelio. This text is published for the first time here with Annie Ernaux’s kind permission. Annie Ernaux wrote this piece in 2016 in response to a photograph taken by journalist Vincent Josse for his project ‘Bus 72’. The photograph shows an elderly woman in the number 72 bus which crosses the richest areas of Paris. Translation first published here on 17 June 2019.