It’s an art photo, oval, glued inside a photo folder bordered by golden edging, protected by an embossed, transparent sheet. Beneath it, Photo-Moderne and the signature of the photographer, E. Ridel. It shows a chubby baby with round cheeks, a pouty mouth, brown hair forming a wave on the top of its head, sitting half-naked on a cushion in the centre of a carved table. The cloudy, sepia background, the table’s carved garland, the embroidered shirt, part way up the belly and with one strap slipped down a plump arm, the whole point is to conjure up a cupid or a cherub, like in a painting. Thus, even though the country was occupied by the Germans, half of the men prisoners, and round-ups of Jews and Gypsies were beginning, people still brought babies to the photographer, to celebrate their arrival into the world with a work of art that all family members, on both sides, would receive a copy of.

Another photo, signed by the same photographer – but the paper in the folder is more ordinary and the gold border has disappeared – intended probably for the same family distribution, shows a little girl between four and five years old, serious, almost sad despite the round face beneath her short hair, separated by a parting down the middle and pulled back by slides with ribbons dangling off them. The left hand rests on the same sculpted table – this time fully visible, in the style of Louis XVI – which raises her shoulder. She’s squeezed into her blouse and her suspendered skirt is rising up a bit in front because of her prominent belly, perhaps a sign of rickets.

All these archival family pieces have to say to me is, “that’s me” – echoing the “that’s you” that must have been repeated when they were shown to me – and also that they belong to the L[1]. time.

The L. time is war, as a normal given of existence. One day, someone said “the war is over.” I was born in the midst of it, its end had no meaning.

That time has no dates, no benchmarks. Only images of places, scenes.

There is the house by the river, below a road running alongside the textile mill with red brick chimneys with iron rings around them. On the ground floor, on the street side, the café runs the length of it, with a pool table you could hide under during the bombings, and the food shop, without any stock. At the back, the kitchen overlooks a paved courtyard, embedded between the walls of the neighbouring houses, except on the side where the river flows at the foot of a low wall with steps built into it so that water could be drawn.

The river is narrow, clear enough for me to see broken dishes, rusty objects, on the bottom. On the other bank stands a tall wooden building, probably the blind back wall of a factory shed. The outdoor toilets were put in above the river. The excrement was gradually washed away by the water as it steadily lapped and beat around it.

From the kitchen, the staircase leads upstairs to the dining room, which is only ever used on Sundays. On the table, a bowl of artificial orange flowers with black stems. Opposite, the bedroom, my little rosewood bed pushed against my parents’ bed, the window onto the courtyard, with a railing to prevent me from falling out. A tiny room, containing a cot, suitcases stuffed with bills. On the street side, another room, bigger, empty.

All the images of the inside of the house appear greyish to me, in the kind of twilight vision that is attributed to cats. Only the dining room table and artificial flowers are in the light. The child I see has no body. She is a little shadow trotting among the big shadows, my parents, clients and soldiers whose comings and goings are constant. Above the little shadow hangs a huge voice, with unpredictable outbursts of anger and laughter, the voice of my mother, the voice of God, which will fall silent forty years later, and only then will I be free.

Far off, beyond the textile factory, further than the church and the Roman Circus, is the public park. Near the entrance gate, a rusty cannon where children climb, picking off snails hanging from it. A huge tree casts a shadow over the sandpit in front of which my mother sits on a bench with other mothers. It is the place for afternoons, sun and unknown children, refugees from Le Havre pounded by bombs – for the blind man who took off his dark glasses, offering two holes lined with skin where his eyes should be.

In this L. time, nothing that resembles thought, only thick, violent feeling, as solid as any object, enclosed in scenes that are often silent, though some are fixed, others moving. A uniformly dark film in which images with no sound sometimes appear:

A trench cut into yellow earth, perhaps on the side of the hill above the river, with planks to sit on. It’s a shelter where you can take cover during the bombings. Someone brought a plate of biscuits.

We’re eating on an embankment in the sun. My mother is wearing a beige dress made of an embossed fabric. Warmth, laughter. Ducks, probably from a nearby farm, and who we threw pieces of flan to, follow us when my parents leave on bicycles. I’m on my father’s luggage rack, my mother is leading the way.

We are on a road alongside a sunlit wood. The sun is gone. Bombers rotate above us, the bikes are thrown down next to the road. My mother dives into in the woods alone, my father stays at the edge, holding me by the hand. I scream and cry. It feels as if my mother is abandoning us and that I’m going to die. Or else she’s going to die.

These two scenes should perhaps not be situated on the same Sunday but I have always associated them, the second following immediately after the first, in a kind of diptych: happiness and unhappiness, one summer Sunday.

We’re outside sitting on benches, in the middle of a crowd. In front of us, on a platform, a woman is being locked into a large box. Only her head, hands and feet protrude. Spikes are pushed through the box from one side to the other. When it’s over, the woman is still alive. The fact of discovering undoubtedly almost immediately that it was all fake, play-acting, didn’t change the feeling of horror felt when witnessing a show that for me, then, was reality. It’s only through an effort of reflection and classification that this image of a woman impaled ceases to be equivalent to the bombing in the woods. Thirty years later, in an old scientific journal, I read the description and explanation of the magic trick, which was apparently very famous before the war, and entitled “A woman’s martyrdom”.

Another diptych.

First image. My cousin, a big girl who already goes to school, climbs up on the table at the end of lunch and sings “Petit coquelicot mesdames, petit coquelicot messieurs” as she makes faces. There is laughter. Everything is dark inside me.

Second picture. She’s reading in the courtyard laundry room, I approach silently from behind her, with scissors, and I cut off one naturally curly lock of hair. Horrible screams, from my cousin, then from my mother. Still clearly seeing the curl, feeling the strength and fullness of the desire of this minute.

Other images, most related to violently desired food, or sex or excrement. These are fascinations: impossible to tear yourself away from the thing seen, and therefore to forget it.

Peaches that my mother keeps in a bag and that I want to eat immediately, “even with the skin”, in the public park. Same desire for red plums, sold in a transparent bag, as if they were big pieces of candy, which my mother buys at a party on a Sunday.

The unknown thing – his penis – that my little playmate took out of his underpants to water the sandcastle we had built together in the street, in front of the café door.

The tongue that a young woman laughingly sticks out at a G.I. in the American camp –where my mother took me for a walk one afternoon – as she turns it blue by wiping an ink pad or a lollipop over it.

A chamber pot whose inside surface is all dirty, as if it had been wiped like a saucepan, in a sick child’s bedroom, the little boy of a level crossing attendant my mother visits.

The biscuits soaked in cider and transformed into a yellow porridge passing back and forth between “la mère Foldrin’s” two remaining teeth, as she sits in the café.

And so on.

For all these images and scenes, no order can be established between them, only one certainty: it was Sunday or not.

And this, though it is neither part of the scenes, nor of the fascinations:

One afternoon, alone at the open window of the room. I scream and a distant voice answers me. Again and again I shout. There, beyond the building, the hidden little girl always answers me but is silent when I keep quiet. I don’t know how or when I discover it was the echo.

I’m walking alone, head down, elbows against my body, along the fences of the small street that goes up to the main road of the textile factory. I reach it, follow it for a few dozen meters, then I go down another small street towards the house. This is the first time I’ve ventured so far alone, violating my parents’ command. I can see the stony ground, so close to my gaze, I can feel my fear and my will to go all the way.

An impression that, these two stories are not about a child, but about self-awareness, distinct from things, and a consciousness of the world.

All through those years, children boarded trains to Auschwitz, the inhabitants of Leningrad ate cats to survive, resistance fighters in the Vercors were shot against trees. In the Warsaw Ghetto, naked corpses were piled up in carts, with their arms and legs folded in. In Hiroshima, thousands of bodies shrivelled up in a few seconds and Colonel Tibbets who dropped the bomb, said that golden dust rose up from the explosion. I saw these images on television. I cannot unite them with the images of L., although they are contemporary. Even when I see them, I can’t believe that I was already alive at that time.

The L. time, which had no beginning for me, ends in the Autumn of 1945, in the front seat of a removals van. My parents had sold the business and returned to Y., where they were born, which they had left fourteen years earlier. It’s a Sunday. The van is struggling to move through the crowds and shacks of a carnival set up amid piles of rubble and demolished houses. The centre of Y. was burnt down during the German advance in 1940, only rubble remains. We’re going to live in two rooms without electricity on an undamaged street near the centre.

As we leave L. I began to remember. The public park, the export trading house by the river, my mother’s beige body on her bicycle, American tanks throwing bags of powdered orange juice into the textile factory street, have all melted into the sunny vision of a day of celebration.

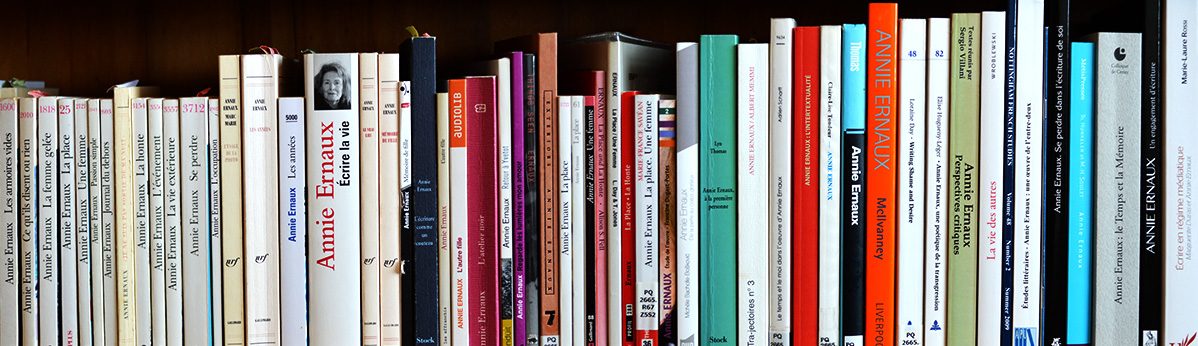

First published in Jardins d’enfance, dir. Clarisse Cohen (Le Cherche midi, 2001), pp. 79-88, reproduced with the kind permission of Annie Ernaux, translated by Dawn Cornelio. Translation first published here on 23 October 2018.

[1] L. refers to Lillebonne, Normandy, where the family lived during Annie’s early years.