The train stops at a station, yours maybe. You search for the name of the station, for some indication of where you are. Even with your face pressed against the window, you can’t make anything out. To see better, you get out. The train sets off, your luggage on board. On the platform there are no station signs. You ask the people waiting what the name of the town is. In a world of their own they look at you blankly, then turn away.[1]

Or there again: you are in the middle of a car park where the rows of cars stretch out to infinity between pillars numbered P1, P2, etc. You know you won’t be able to find your car, you’ve forgotten the number of the pillar.

But you are not dreaming: it’s Y.

It is there on the road maps. Forty kilometres from the Eiffel Tower, fifty from Versailles. The guidebook says there are 100,000 inhabitants. There’s a train there from Saint-Lazare every half an hour. There’s a turning for it off the motorway. In the summer, approaching from the south-west, you wonder if you’ve spotted in the distance some white monumental necropolis, suspended in the misty air.[2] The motorway dives down between steep grassy embankments. A mirage. There’s no town here. Slabs of buildings dotted on the horizon, a long way away. Red cranes swaying gently in the sky. A long glass wall of shimmering smoked-glass panes like giant Ray-Bans, reflecting things that no-one actually sees.

S M

NUMBER 031 38 43

Flat surfaces with letters and numbers, empty spaces full of weeds where supermarket trolleys lie, their wheels in the air.

A black cube of rust: 3M MINNESOTA.[3]

Already you’ve no longer any idea where you need to go.

They’ve done it on purpose so you don’t have time to look around you, to wonder in amazement what on earth this is. At each junction, six arrows in succession for each direction. By the time you’re at the first, it’s too late. You’re already on the way to rejoining the motorway that you’ve only just left or to entering a no man’s land lined with incongruous signs, such as ones for the regional banking group Crédit Industriel et Commercial, metal welding and repair companies, special schools, and ever onward, down roads with no names, full of glinting potholes.

It takes days to learn how to stop being constantly pushed back towards the outer edge. Kilometres of suffering deep anxiety in the middle of streaming cars which lead you on in their direction all the better to lose you. You finally understand that here the walls will always recede. You will never reach the tall Blue Tower block[4] – there right in front of you – by going straight towards it. You need to learn to find the guiding thread leading to each building, to navigate the labyrinth of motorways encircling the walls. To work your way fearlessly down roads hemmed in on all sides by mounds of earth, routes that always lead you – by figures of eight and multiple twists and turns – to a car park. It takes months to learn that. Eventually you do it unconsciously, driving alongside the steep embankments, at the foot of the shadows from buildings, under the enormous footbridges for pedestrians, from which children coming out of school spit nonchalantly to impress. Every time, you notice, on the outside of the bridge, the mistake made by the vandal, whether stupid or in a rush, who has painted in red from left to right a stark insult directed towards no-one in particular: KREJ.[5] They don’t need to worry: all you’ve got in your head are roads going round and round.

No-one ever walks along the roadsides. On Sundays men and women in shorts jog, chins up. At every bus shelter there’s a small group of people who’ve come down from the footbridges – in the afternoons, women in flowery African robes and sarees, in the evenings, men in outmoded jackets, with bags slung over their shoulders. The green and white vans of the Green Spaces gardening company go tirelessly up and down the roads, gardeners in green overalls cutting the grass and hoeing the flower beds on the verges.

Smooth coloured walls intensify both the light and the wind, and give rise to shadows longer and darker than elsewhere, extending an icy invitation to the cold air. Car parks, buried underground, covered, suspended in space. Only the rumbling of cars. Sounds and smells dissolve. Sounds evaporate in the air the minute they are emitted: silence reigns. The planners’ aim was to cut out echoes: building facades tilted back towards the sky, stepped balconies, offered up to the wind.[6] Not smoothly aligned structures bursting with cries and laughter. Nobody calls out to anyone here, the human voice does not carry. The silence of a hundred thousand inhabitants, marooned on thousands of hectares of farmland, brought together in housing blocks like magnetic field lines[7] in the middle of woods and grassland. Out of sight.

They’ve come from everywhere, those who don’t know where to go, who don’t have enough money to settle down in the upmarket areas of cities. They are gasping for air on the interminable Argenteuil Road or beneath the flyover at the Patte-d’Oie d’Herblay.[8] They showed them brochures of air-brushed residential areas. For once it was true when they said: ‘You will have it ALL’.

It’s all here:

council offices children’s nurseries cinemas

town hall kindergartens theatre

tax office special school swimming pool

railway station secondary school ice rink

social security technical college music school

post office job centre recreation camp

electricity & gas boards

family gardens

etc.

Everything’s been put together in the same area as if the buildings were constructed like blocks on an organisational chart. Quadrangles, triangles, cubes, cylindrical shapes made to appear merely fanciful and disordered, and in colours to make you feel cheerful. But in the sort of blue, cool green and black to inspire a respectful attitude towards the institutions, so that you would not dream of entering the Cultural Centre in the same way as you would some sort of seedy dive. Here is to be found the sum total of all the needs of men, women, babies or dachshunds, whether social, educational, administrative or informational – serious needs they can sort out on computers, or can socialise in community centres or clubs. Managed. Socially acceptable needs, no burgers and chips from a kiosk near the library, no bar on the station to swig a drink and have a piss while waiting for the train.

And above all, the most important, crucial, thing of all: shopping. When there was nothing here but beetroot fields, they erected this cathedral of smoked glass, the shopping centre of the Two Fountains,[9] where it never rains, where there is never the light of day, where it is neither hot nor cold, but where fish goes bad more quickly. The sound of footsteps and the smells have been stifled. You can find everything here, thanks to the Samar superstore, where they mind your babies in a crèche so you can shop hands-free. Teenagers and the unemployed can spend all day there, sat on the edge of the fountain or reading comics at the Temps de Vivre bookshop. The police circulate at a nonchalant pace. At the top, through the plate glass, you can see the motorways, the tower blocks, through a dreamy Indian pink. It is the only landmark building round here that holds an annual celebration, with massive discounts and ‘special offers’.

They have looked after the children with touching solicitude. Schools in psychedelic colours, no more streets with cars and crime, but rather safe alleyways covered with plants – firethorn and broom – down which they cycle, play, walk to school, sheltered from the world. The parents remark with amazement: ‘They’ve done everything for the kids.’ Finally relieved to have brought them into the world and not to have to worry about them any longer. Reassured: no drugs, no prostitutes, no pavements.

There is never a MISTAKE. Three porthole windows, one bay window, two narrow slits, then again three portholes, etc. Teaser: continue the sequence.

They have managed the needs of space, light and enjoyment. In the fields, in the hollows, on the hills, they have positioned blocks of flats coloured pistachio green or detergent blue, marina-like terraces with arches but without the water,[10] English cottages in candy pink with thirty centimetres of lawn, complementing the surrounding woods, residences 80 metres square with sloping mansard roofs and small leaded windows. They reckoned that you did not need space inside when there was so much of it outside, that you would have to take the bus or go by car to buy your daily loaf of bread. As for names, they opened a thesaurus at ‘housing’ and ‘woods’ and called the blocks the Terraces, the Pergolas, the Balconies, the Groves, the Glades, the Oaks, exhausting one category before moving on to another. Then, as if in playful mode, subdividing the classification of each block into colours: the Chestnuts – mauve, purple, brown, turquoise, etc; the Ten Acres – pink, ochre, beige, etc, etc. And the internal streets are all named after flowers.

But there are no chestnuts at the Chestnuts, no poppies on Poppy Street and the rosy cottages are white. They have separated the words from the things, put words in place of things, so that you can live in a romantic dream, so that you do not search for any real meaning. And so that you will forget that the Arabs only live in blocks of flats for Arabs, that the skilled workers live in buildings for skilled workers, that two-income executive couples live in homes with a mezzanine and a fireplace. That every morning women from the Arab block F5 go and clean the terracotta tiles of the homes with a mezzanine, under the lazy gaze of a dog.

A dream-like place. The train from Saint-Lazare doesn’t go any further than Y. It comes to a halt below ground alongside a gigantic leg in jeans intertwined with a bare leg leading up to an item of green and white gingham-checked clothing with the buttons undone. When you reach the concourse at the top of the escalator, you catch the rest of the image you saw down below, the displaced top halves of a man and a woman, in such a way that you see her unfastened blouse. They are making love in the flowers.

It is just about the only mural painting around here. Elsewhere, on the walls, no scene, no face, not even a sketch. The only thing to be found, on an ordinary ten-storey block of flats, visible from afar, in violent tones of red and blue, is – perhaps – a telephone or a seahorse. Or, rather, perhaps it’s a penis.

Writers and TV people come from Paris to see Y. Already, Victor Rhubarbe, Marie Vicaire, Morosi and Anne-Marie have been here. They visit all the amenities, the Cultural Centre, the schools. And the children have a good laugh at missing an hour of classes, at being photographed or being on the telly. The visitors go back to Paris saying: ‘The children looked so happy’ or ‘It’s the town of tomorrow.’ They never return.

Nothing makes the inhabitants of Y stand out. They read the Parisien libéré newspaper, do the lottery and go to the cinema on Saturday or Sunday. But they never know how to show anyone the way. Someone asking for the small Cornflowers Street plunges them into confusion, they have after all only just arrived here themselves.

Hardly anyone dies here, except, as it happens, Hakim, two days old. There are only births. There are no old people. So no old sayings or gestures, such as ‘pulling up your girdle with both hands’ to get it back into place, or saying in jest to a child: ‘I’m going to chop off your ears!’ No shameful things of the past here, no beggars, no drunks. Everyone strives to look just like the houses – to be clean and bright, as if in marketing brochures, with all the men employed by Crédit Lyonnais and the women demonstrating stockings made by Dim. Everyone is calm. They get off the train without running, bump into you quietly and unapologetically, buy flowers and mushrooms on the station concourse, and then get into their cars and buses towards their holiday-like villages. At the counters in the bank or the post office, at the supermarket checkout, they form interminable queues without complaining, not even under their breath. In their apartment blocks they have representatives of the residents’ association to do that. Never a dirty look. Decent people, they don’t turn to face the cops picking up a young boy or towards someone in tears. Every year children drown in the midst of bathers at the recreation park.

They don’t scrawl much on the walls, except things like this response, at the bottom of a poster ordering people to ‘Look after your own affairs, self-management’: I HAVE NEVER DONE ANYTHING ELSE.

Every morning a glittering pile lies at the foot of a bus shelter. During the day, the bus shelter company replaces the glass panel, making use of the opportunity to stick over it a new publicity flyer: ‘Roar for joy.’[11] In all the nooks and crannies of darkened walls and flights of steps there is the smell of urine, the only smell the wind around here doesn’t take away – and it is topped up every night.

They told me: ‘It’s there.’ I was there without having gone anywhere. I was scouring the streets, the shop windows, the people, worst-case scenario something like La Défense. I couldn’t see anything except the big glass wall that was reflecting the clouds, building blocks randomly placed over an endless space. Ruins, perhaps.

The wind was sweeping around the Blue Tower, the facades twirling around like green pinwheel mints,[12] in front of the entrance to the Two Fountains. Once through the door, I was losing touch with my physical body. Simply an upward gaze, head high. After a while a voiceover runs in my head, the only part of me resisting dissolution: ‘It’s me, this is me…my hair down my back…I am walking towards the supermarket… .’ In Monoprix, the light is so white, so blinding that I thought I had been propelled on to a stage and did not know my role, nor the movements I was supposed to carry out. Taking packets of pasta and milk off the shelves was demanding an effort of memory. I went back to the alleyways inside the shopping centre which were plunged into a semi-darkness. People were sliding around noiselessly, just murmuring, drab in comparison with the shop windows of dresses and perfumes, even the hardware shop seemed luxurious. Some women were simply in perfect harmony with the place, red lips, red boots, flowing mane of hair, neat buttocks firmly encased in jeans as they moved forward determinedly. The New Woman. It seemed to me that I no longer had any history and nor did anyone around me. I was emerging like the first time you go out after a bout of flu, the air does not hold you up. Better not to look around you, the car park stretching to infinity, 3M Minnesota, red cranes, just keep on walking. I would shut myself up in my car. It was all I had to protect me from space, from the blue and green walls. From weightlessness.

I’ve got used to this place with no past. Just don’t raise your head, don’t stop at the foot of the Blue Tower, don’t look up at the sky. Cross the windswept squares with your inner voiceover, don’t look up, and get back home to orange Paradise. You don’t feel you’re getting older here. Ageless, like everything else round here. New or ageless, it’s all the same, and you never stop being in the newness of it all. Nothing existed before you, neither roads nor houses. A space without time.

Sometimes I still ask myself what Y resembles. What kind of human dream it represents.

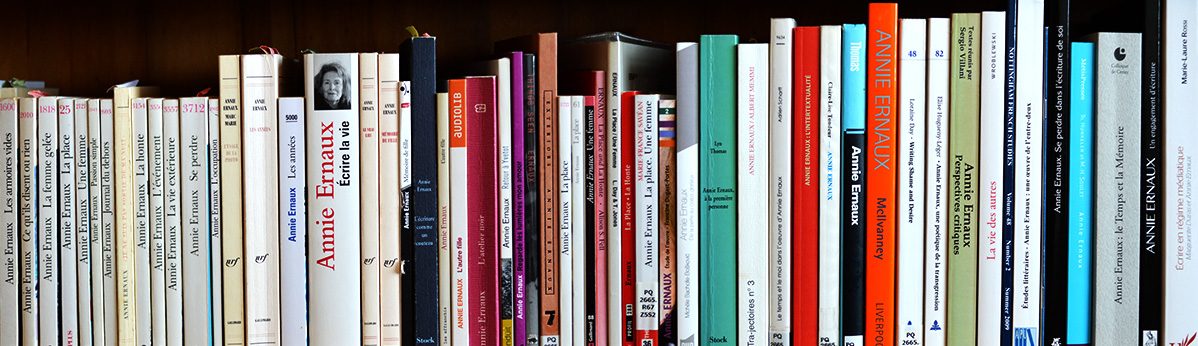

First published in French in ‘Roman’ 5 (‘La génération introuvable’), autumn 1983, pp. 27-35. Translated and reproduced here with Annie Ernaux’s permission.

Translated by Jo Halliday. Translation first published here on 21 August 2025.

[1] NdT/Translator’s note: This piece pre-dates and identifies themes developed in more detail by Annie Ernaux in her later published Journal du Dehors (Gallimard, 1993)/ Exteriors, trans. Tanya Leslie (Seven Stories Press, 1996) and La Vie extérieure (Gallimard, 2000)/ Things seen, trans. Jonathan Kaplansky (University of Nebraska Press, 2010). See also extracts on this site.

[2] NdT/Translator’s note: See, for example, https://www.sortiraparis.com/en/what-to-visit-in-paris/walks/articles/296723-discover-the-axe-majeur-in-cergy-95-for-a-beautiful-stroll-less-than-an-hour-from-paris, albeit some of these images of Cergy (on which ‘Y’ is based) post-date 1983 – the date of Annie Ernaux’s text.

[3] NdT/Translator’s note: The French/European hub of the American company manufacturing scotch tape, post-it notes, adhesives, plastics, etc was built in Cergy in 1976 and nicknamed ‘un tas de rouille’ (a pile of rust) due to its dark brown colour.

See https://charlottedepondt.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/ETHN_031_0031.pdf and https://j2rauto.com/non-classe/3m-en-france-60-ans-de-culture-de-linnovation/.

[4] NdT/Translator’s note: See https://archives.valdoise.fr/documents-du-mois/document-une-tour-bleue-dans-la-ville-28 ; https://www.batiactu.com/edito/tour-bleue-cergy-adopte-teinte-irisee-49042.php.

[5] NdT/Translator’s note: The writing is the French insult CON which backwards reads NOC. I have translated this as JERK, which backwards reads KREJ.

[6]NdT/Translator’s note: For examples of stepped/staggered terraced housing blocks, see

https://parisisinvisible.blogspot.com/2009/02/hygienic-housing-part-2.html.

[7] NdT/Translator’s note: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo/magnetic-lines-of-force.html?sortBy=relevant.

[8] NdT/Translator’s note: La Patte-d’Oie d’Herblay is a commercial area at a busy crossroads https://actu.fr/ile-de-france/herblay-sur-seine_95306/patte-doie-dherblay-trois-ans-travaux-mettre-fin-bouchons_16737984.html This picture from 1972 shows that there was a flyover (autopont) there at that time which the author calls a ski jump (tremplin). https://rechtempsperdu.canalblog.com/archives/2014/07/17/30269647.html.

[9] NdT/Translator’s note: This is based on ‘Les 3 Fontaines’ in Cergy, see https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Les_3_Fontaines.

[10] NdT/Translator’s note: The author is referring to the style of buildings that tend to be built around new pleasure ports, even though the buildings she is referring to are not overlooking water. For examples of the style, see these pictures of Port-Clergy built, albeit later, in 1991 https://portcergy.com/en/.

[11]NdT/Translator’s note: ’Rugir de plaisir’ was the slogan of the French version of the Lion chocolate bar introduced by Nestlé in the late 1970s. See https://www.nestle.fr/nosmarques/chocolatconfiseries/lionchoco. The French slogan was not translated into English or used in English marketing, so this is my translation.

[12] NdT/Translator’s note: See https://yupik.com/fr/green-pinwheel-mints-p80080.